The crisis is known by many, but truly seen by few — perhaps, until now.

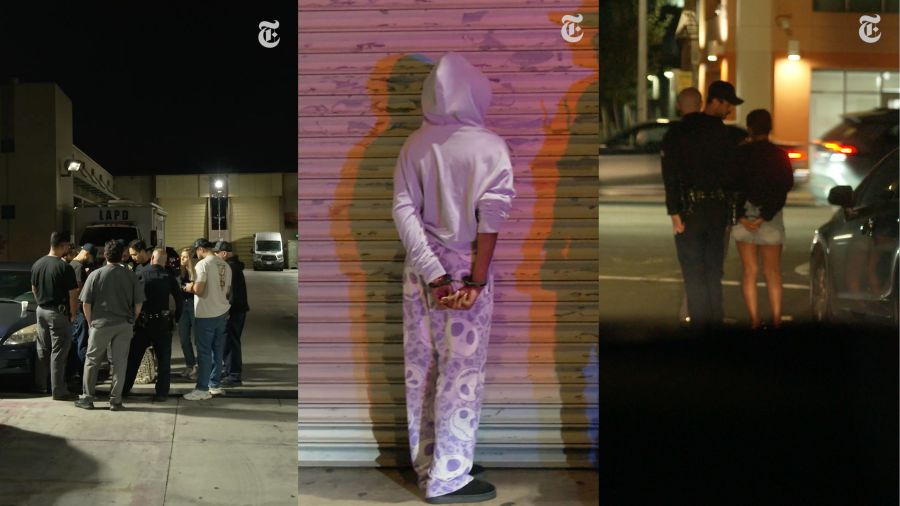

Sex trafficking in Los Angeles operates in plain sight along a wide stretch of Figueroa Street, otherwise known as “the Blade.” Drivers looking for sex idle at curbs and roll down windows while traffickers watch from side streets, directing the girls they’ve recruited—some as young as 11—to meet nightly quotas.

Although the sex trafficking blight of South Central L.A. is widely known, its inner workings remain a mystery to most people. That changed on Oct. 26, when New York Times national health correspondent Emily Baumgaertner Nunn published a sweeping, two-and-a-half-year investigation that followed three women bound by the same fight.

The author

“This story was a reporter’s dream, because everything was firsthand,” Baumgaertner Nunn told KTLA. “It took years of building trust and getting officers to agree to a ride-along. Once I was embedded, I could sit quietly in the backseat, watching them work as if I wasn’t there.”

Baumgaertner Nunn’s piece titled “Can Anyone Rescue the Trafficked Girls of L.A.’s Figueroa Street?” follows three central figures: a sex-trafficking survivor, a Los Angeles police officer determined to rescue underage girls and Shannon Forsythe, faith-based advocate fighting to help them rebuild their lives.

“When I set out to report this story two and a half years ago, I had no idea that ultimately it would be a story about three very powerful women doing what they do best to try to uproot this issue,” said Baumgaertner. “It gave me hope to see the people who show up day in and day out to combat this, even against all odds. And I don’t think that every story has that seed of hope at the center of it.”

Through her investigation, Baumgaertner Nunn also exposed the systems that make Figueroa Street’s cycle nearly impossible to break. Many of the girls come directly from California’s overwhelmed foster care system — often without stable housing, consistent caseworkers or long-term recovery options once they’re found. Even when they are rescued, most end up back on the same streets within weeks.

“No matter how many girls you save,” Baumgaertner Nunn said, “if the system they return to is still broken, the cycle just resets.”

The survivor

The New York Times story starts, focuses on and ends with a sex trafficking survivor, Ana, whose real name is withheld from the story for her protection.

Ana was first trafficked and put on Figueroa Street at age 13, alongside her 11-year-old sister. “Their story had been unoriginal, at least for this street: foster kids turned runaways turned recruits, drawn in by a new friend on Instagram who offered to help them get by,” Baumgaertner Nunn wrote.

Ana had spent years cycling through the system — bouncing between the Blade, motels and short-term housing. Each time she was pulled off Figueroa, she eventually returned, drawn back by the same forces that had trapped her there as a child: fear, manipulation and the absence of a real alternative.

“Many of these girls have never known stability — for some, it’s the first place they’ve ever had someone waiting for them at the end of the day,” Baumgaertner Nunn said. “One of the hardest truths of this story is that no matter how much you want to see a clean rescue, it’s never that simple. Healing isn’t a straight line — it takes time, and people who don’t give up.”

Now, at 19, Ana is safe. She lives in a recovery home operated by Run 2 Rescue, the faith-based nonprofit whose volunteers helped bring her off Figueroa last year. She’s surrounded by counselors, nurses and mentors — women who have walked the same path she did and made it out.

Baumgaertner Nunn said Ana has begun volunteering with anti-trafficking efforts herself. “She’s already helping other girls,” she said. “She’s joyful, she’s funny, she’s strong — and she knows who she is now.”

That recovery was made possible in large part by Shannon Forsythe, founder of Run 2 Rescue. In addition to speaking with Baumgaertner Nunn, KTLA also interviewed Forsythe about her years working alongside law enforcement to help victims escape “the Blade.”

The rescuers

One of the three central figures in The New York Times story — alongside Ana and Los Angeles police officer Elizabeth Armendariz — Forsythe has spent more than a decade working to reach victims in the only place they can be found. As the founder of Run 2 Rescue, she partners with LAPD’s human trafficking task force and local nonprofits, showing up night after night with what few others can offer: consistency, compassion and time.

Officer Armendariz, who KTLA has reached out to for interviews, continues to lead the LAPD vice unit focused on Figueroa. In Baumgaertner Nunn’s story, she’s portrayed as tireless — pulling long shifts, organizing undercover operations, and doing everything she can to convince girls to come with her rather than their traffickers. But her work is often met with painful setbacks: limited staffing, cases dropped in court, and girls who vanish before help arrives.

Forsythe, who often meets the same girls after Armendariz brings them in, takes a different approach. Unlike law enforcement, she doesn’t come with handcuffs or questions. She comes with backpacks, blankets and patience. “We meet them where they are,” she said.

“These victims have been hurt by adults their whole lives — betrayed by the very people who were supposed to protect them,” Forsythe said. “So when I meet them, who am I to think they should trust me when everyone else has proven them wrong? We have to work against that.

“At Run 2 Rescue, we don’t give them pat answers or tell them we have the solution — they’re tired of hearing that. We just meet them where they are. Maybe they don’t want help that day. That’s okay. I’ll say, ‘Here’s my number — call me if you need a meal, or some clothes, or hand warmers… or if you just need a break.’”

A “break,” Forsythe told us, can mean a night off the Blade, a pause from the endless cycle of sex work, violence and fear. For some, it’s the first moment of safety — or childhood — that they’ve ever known.

The rescue efforts

When girls do reach out, Forsythe and her team bring more than supplies — they bring comfort. Each rescued girl receives new clothes, soft sweats and a fuzzy blanket, along with a stuffed animal or teddy bear.

Forsythe recalled several girls who left a lasting mark on her team. There was J., who spoke softly about wanting to finish high school while she waited for social workers to arrive. “She was just so sweet,” Forsythe said. “She got caught up with the wrong crowd, but you could still see that hope in her.”

Then there was K., just 17, fiery and independent. “She feels like she’s raising herself,” Forsythe said. “The second time she came into the station, she walked down the hall with one of our bracelets on, saying, ‘See, I still have my bracelet — I’m going to call them when I need something!’”

And then came W., a girl brought in on a probation warrant the night Baumgaertner Nunn filmed her final video for The New York Times.

At first, W. was angry and cold, refusing to engage. But after Forsythe offered her clean sweats and fuzzy socks, she began to soften. As they talked, W. shared that she’d been praying for someone to really see her — and in that moment, Forsythe said, she finally did. Moments later, W. broke down crying and rested beside her, “just a kid again,” Forsythe said.

For their safety, the girls’ names are identified only by their first initials.

The rest of us

Forsythe says the fight against trafficking begins in the community — with neighbors who learn, listen and refuse to look away.

“These are kids,” she said. “If you look at them first like someone’s daughter or sister, your entire perspective changes.”

That shift — from judgment to understanding — is what she said Run 2 Rescue tries to inspire through its outreach and training programs. The nonprofit hosts “Human Trafficking 101” workshops to teach community members how to recognize warning signs and safely report suspected exploitation. Those interested can register here.

“The more I reported, the more I realized this isn’t just a police issue or a policy issue,” Baumgaertner Nunn said. “It’s a community issue. It’s about people learning to see what’s right in front of them — and refusing to look away.”

Volunteers can also help assemble recovery kits for newly rescued girls — each one filled with a hoodie, sweats, fuzzy socks, slides, a stuffed animal, a blanket and a backpack with essential items like toiletries.

“Everyone has a part to play,” Forsythe said. “Not everyone can go out to Figueroa at night, but you can be a voice. You can learn the signs. You can help foster a young adult who’s been overlooked.”

“Awareness alone can change outcomes for these girls,” Baumgaertner Nunn said.

Run 2 Rescue’s annual Stockings of Hope program has already been fulfilled for the season, but the organization is still accepting Christmas gifts for survivors through its Amazon Wishlist.

Each gift, Forsythe said, carries the same message she’s been telling girls for more than a decade: “You’re seen. You matter. You’re not forgotten.”

“That’s what gives me hope,” Baumgaertner Nunn added. “People who care enough to stay — to keep showing up, even when it’s hard.”