Walt Disney simply tapped his fingers as Burbank’s elected leaders offered up reason after reason for why his proposed amusement park – Disneyland – shouldn’t be in their city.

“We don’t want a carny atmosphere,” one councilmember said. “We don’t want people falling in the river, or merry-go-rounds squawking all day long.”

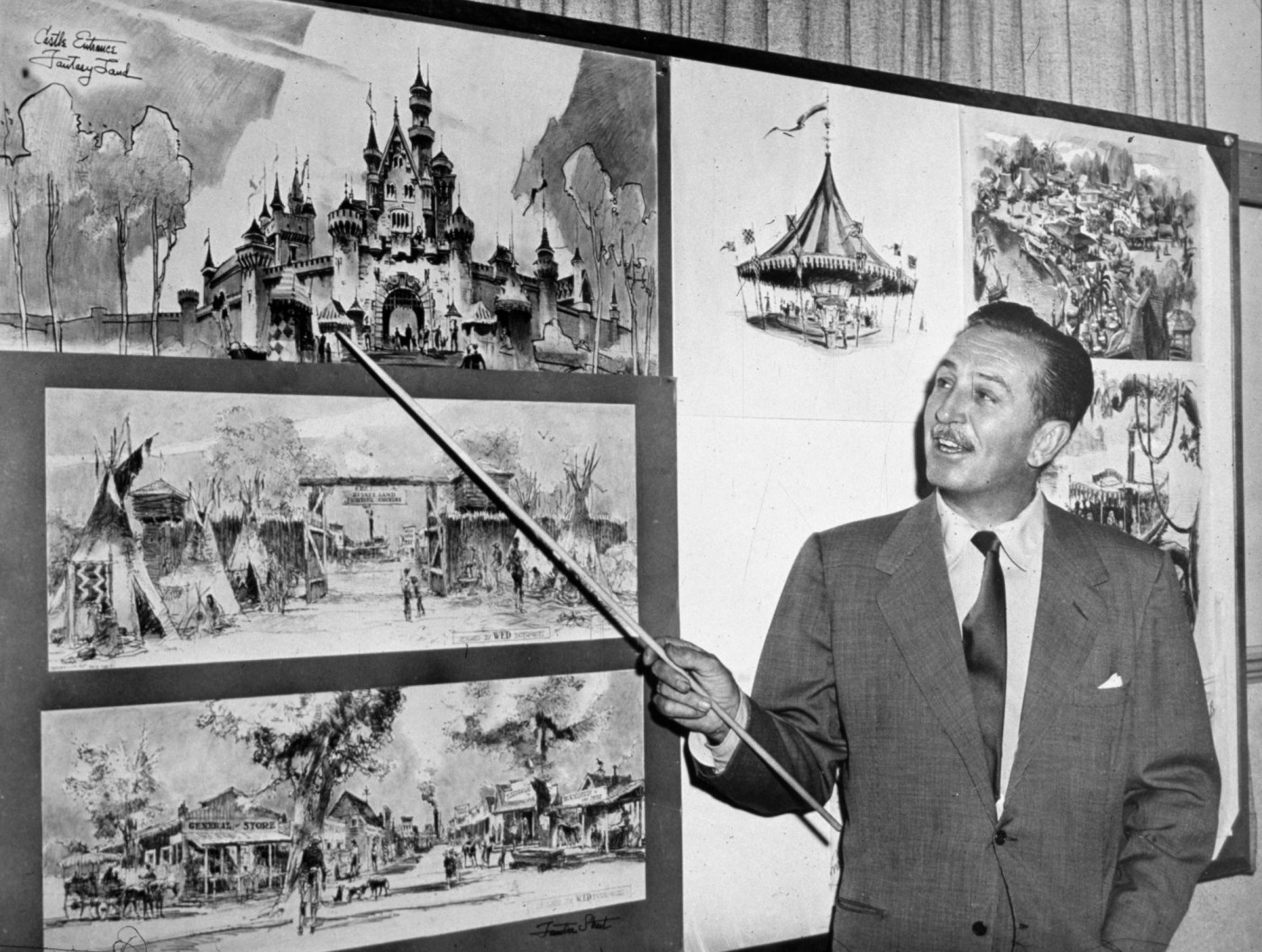

When it was over, Disney and an artist who had joined him at the public meeting, Harper Goff, gathered up their drawings and left in disgust, according to an account in the 2008 book “Working With Walt.”

That was September of 1952. Over the next two-plus years Disney – then a 14-time Oscar winner and one of the best known men in America – would get a very different hearing from officials in Anaheim and Orange County.

Anaheim’s leaders, unlike their counterparts in Burbank, didn’t trash talk Disneyland. And county officials welcomed him. Disney responded, as his ambitious project got going, by engaging local leaders and doing business with local companies.

As a result, by the time Disneyland’s gates opened, on July 17, 1955 — on former orchards just inside the recently expanded city limit of Anaheim — Disney and Anaheim happily entered one of the great corporate-civic marriages in American history.

See also: Disneyland 70th anniversary timeline from 1955 to today

What has their marriage changed? More than you might think.

Real estate? Disneyland helped spark a mid-century re-invention of Orange County, which soon became a center for master-planned (Disney-like) communities such as Irvine and Laguna Niguel and Mission Viejo. Similar towns can be found in Arizona, New Jersey and China, among others.

Entertainment? Disney, post Disneyland, expanded into everything from live-action movies to streaming services to cruise ships, becoming the template for modern entertainment conglomerates.

Government? Disney’s connection to Anaheim sometimes has drawn unflattering critiques, with the company viewed as overly powerful and the city as overly welcoming. Critics say it’s helped to pave a path for corporate influence over municipal governments. Whether that’s fair or not, Disney has become far more intertwined in civic life in Florida, at times holding approval rights and responsibilities over development and community services on some Disney-owned property in that state.

But for all that, the marriage of Disney and Anaheim has been, if not romantic, mutually transactional.

Anaheim was shedding its agricultural roots before Walt’s arrival. Door locks, paint, steel and aerospace — not farming — were the city’s top industries. But, before Disneyland opened, Southern California’s biggest freeways didn’t yet reach deep into Orange County. And the idea that Anaheim might be a tourist destination was laughable.

“Anaheim was that little town on the way to the beach,” said Keith Murdoch, who was Anaheim’s city administrator and city manager from 1950 to 1976, in the 2007 documentary “Disneyland: Secrets, Stories and Magic.”

Likewise, before expanding south, Disney’s company wasn’t yet what it would become.

Though wildly successful as a producer of animated movies and shorts, and maker of documentaries that touched on themes of nature and history, Walt Disney’s basic goal was both simple and profound — he wanted to extend his movie-experiences to something approximating real life; a place like Disneyland.

He also wasn’t above a little revenge.

“I think that (Disney) took a great deal of pleasure in taking (Disneyland) elsewhere after the reception he got” in Burbank, Goff recalled in a 1979 interview.

Over 70 years, Disney and Anaheim’s mutual needs have been a key part of Orange County’s evolution from an agricultural suburb of Los Angeles into a stand-alone urban center, the nation’s sixth most populous county with an economy that federal data recently pegged at about $333 billion a year. The marriage also helped turbocharge Disney’s studio into something that today sells everything from costumes and condominiums to theme park tickets and plays and movies in every corner of the globe. Currently, Walt Disney Co. has a market cap of about $215 billion.

But when Disney came to Anaheim he wasn’t exploiting any rubes. Both partners entered the marriage with the idea of profiting off the other.

“We were looking to improve the economic status of the city by attracting new industries,” Murdoch said in yet another film, the 2009 documentary “50th Anniversary of Tomorrowland.”

“We looked at Disney as another industrial opportunity.”

Over the decades the relationship has shifted and re-shifted and re-shifted again, with Disney at times viewed as a corporate overlord and Anaheim seen as a vassal state. But Disney money – tax revenue created by Disneyland and Disney-related projects – has helped fund everything from Anaheim schools and parks to street repairs and semi-affordable housing.

And while Disney frequently has strayed outside of Anaheim – building theme parks in places like Florida and France and China – it’s also continued to grow locally.

In 2001, Disney California Adventure opened next to Disneyland. And, since then, the company and the city have worked together to transform the model from “theme park” – with visitor money mostly staying on Disney-owned properties – into something they both describe as a “resort,” with visitors using hotels and restaurants near Disney-owned properties but with taxes going to the city.

“When Walt Disney chose Anaheim to build Disneyland, he worked with leaders who had a bold vision of what the city could become,” said Cathi Killian, Disneyland Resort’s vice president communications and public affairs, in a prepared statement dated July 11.

“Over the last seven decades, we’ve been fortunate to continue those relationships, which in the ‘90s helped transform the park into the resort destination it is today. Now, with the approval of DisneylandForward, we look forward to a bright future with meaningful investment and growth that will benefit the community we call home.”

‘Wonderful World?’ Sometimes

After Burbank slapped down Disney’s theme park idea, the cartoonist hired the Stanford Research Institute to find the best location for his park, a long held dream that he wasn’t surrendering.

Economists looked at traffic patterns and freeway planning, population growth – even access to power and sewage. The best sites, the group said, were in Orange County, a community next to a huge population center (Los Angeles) that was in the early stages of a boom. And the best of the best, they said, was a tract near Ball Road and Harbor Boulevard.

But after Disney put down a deposit on that land – at a number considered generous – the asking price for a neighboring property shot up.

At that point, according to “Disney’s Land: Walt Disney and the Invention of the Amusement Park that Changed the World,” Disney decided he “had to form an alliance with the city government.”

“(Walt Disney) had a vision,” said former Anaheim Councilmember Stephen Faessel, who has written several books about Anaheim’s history.

“Anaheim’s leadership, at that point, embraced that vision.”

Disney soon built a rapport with downtown businesses.

“He engaged some of our local insurance companies. He bought stuff from local builders. He bought lumber from Ganahl Lumber. He bought hardware from the old Martenet,” Faessel said. “So he tried as best he could to build a business relationship with Anaheim businesses, which was certainly appreciated.”

That business relationship would boost both sides.

Disney — who pitched Disneyland every Sunday night on his national TV show, “Wonderful World of Disney” — sold a lot of theme park tickets. In the second half of the 1950s, Disneyland was drawing about 5 million people a year.

That, in turn, helped boost Anaheim. In the last federal head count before 1955 Anaheim’s population was about 15,000; by the 1960 Census it was more than 104,000.

But it wasn’t just people. Hotels and restaurants; roads, schools, parks — all were opening in Anaheim during a time when Disneyland was becoming a national household name and, increasingly, a bucket list item for every kid in America. Tourism to Anaheim — and to nearby beach communities like Newport Beach, Laguna Beach and Huntington Beach — expanded rapidly in the ’50s and 1960s.

Anaheim even joined the big leagues.

In 1966, the year the Angels moved from Los Angeles to Anaheim, the city was by far the smallest to host a Major League team.

Those other towns might’ve had more people, but they didn’t have Disneyland.

Walt Disney and the Angels owner, cowboy actor and crooner Gene Autry, were long-time friends. Disney sat on the Angels board of directors when the team first joined the American League, in 1960, and he was a voice on the board as several cities — notably Long Beach — wooed the Angels.

Disney reportedly pushed hard for Autry to choose Anaheim, and he played a role in the development of Anaheim Stadium.

Disney died in 1966, but his company remained connected to pro sports in Anaheim.

The Disney Corp. was the first owner of the Mighty Ducks hockey team, which started play in Anaheim in1993. And in the mid-1990s Autry sold a 25% of stake in the Angels to Disney Corp., which took an active managing role in the organization. By 1998, when Autry died, controlling interest in the team went to Disney Corp., which owned both of Anaheim’s pro sports teams until the early 2000s.

During that same period, Disney was expanding. The company opened Walt Disney World in Orlando, Florida, in 1971. It opened another park in Tokyo, in 1983, and Euro Disney, in Paris, in 1992.

But expansion in Anaheim was left out.

Though attendance didn’t rise every year, the trend line at Disneyland was pretty strong. By the mid-1990s, the park, which in the early years closed a couple days each week, was a 365-day-a-year operation bringing in more than a million visitors a month.

The park’s popularity — and a growing desire for more of everything in Orange County — brought the company’s focus back to Anaheim. A second theme park, locally, felt inevitable, said former Anaheim Mayor Tom Daly, who served on the City Council from 1988 to 2002.

But there were hurdles.

Though Disneyland was well maintained and marketed as relentlessly happy, conditions in some neighborhoods close to the park were blighted. The area now known as Anaheim Resort was grim, and life on parts of some of the bigger streets near Disneyland included everything from prostitution and drug use to rampant poverty.

“The condition of Harbor Boulevard was a big deal,” Daly said. “It was a major embarrassment.”

Daly said the focus was on removing blight and improving the area’s infrastructure. Design standards were set, utility poles were put underground and new freeway ramps were built leading into a massive new parking garage.

In 2001, the city opened a second Anaheim park, Disney California Adventure.

The city took out $510 million in bonds to finance its contributions for the project and Disney invested $1.4 billion. The resort area — and the concept — were established.

It also became the subject of heated civic debate.

The city’s deal let Disney pay rent of just $1 a year for that parking structure. The company also got to keep parking revenue and take ownership of the lot when the bonds are paid off.

Daly and others defend the deal. But, fair or not, the low rent — and Disney’s long-term profit — remain a flashpoint for people critical of the city’s marriage with Disneyland.

Still, since that expansion, hotel tax revenue in Anaheim has skyrocketed. In the late 1990s, the city was getting about $45 million a year in hotel taxes. Last year, it was about $240 million.

“It’s easy to criticize, but on par, Disneyland powers the hotel stays in Anaheim,” Daly said. “And you look at the growth of bed tax revenue over time, it’s breathtaking.”

The bonds the city took out will be paid off in about two years. After that, the city will have more than $120 million a year for public projects.

That foundation, was set by the 1990s expansion that has turned Disney into the county’s largest employer (passing UC Irvine) and the linchpin of Anaheim’s economy.

To infinity, and…

If the tone of the last two decades of Disneyland and Anaheim’s marriage was set by the 1990s expansion, the next 40 years could be influenced by the city’s recent move to approve DisneylandForward.

In one sense, the plan is simply a zoning change. Over the next four decades, Disney will be allowed to develop Disney-related projects on its parking lots, building new parking as needed to accompany revenue- and tax-generating developments.

But it’s also bigger than zoning. At its essence, the council’s unanimous approval of DisneylandForward means the Disney and Anaheim marriage will continue, at least somewhat amicably, for the foreseeable future.

For most residents, the promise of tax-generating Disney experiences — everything from theme park-esque attractions to hotels and restaurants — figures to boost city revenues.

For local business owners who depend on Disney-oriented tourism dollars the deal means security. The floor for Disney spending over the next decade is $1.9 billion.

“This is really going to be a tremendous destination for people,” said Bharat Patel, whose family has owned Castle Inn & Suites on Harbor Boulevard since 1989.

If Disney builds new attractions or retail or anything that might bring in tourists — and if Anaheim’s other major developments, like OCVibe, succeed — Patel sees a future with more visitors staying longer and spending more. He even compared his town to “vibrant destinations” like New Orleans and Los Angeles.

Patel has lived through decades of such changes. He remembers the days of tired families in station wagons driving into the parking lot at his family’s inn, in the middle of the night, looking for a place to sleep. They’d ring the bell, waking his father, who’d groggily get them settled into a room.

“It was pre-internet,” Patel said. “People would either have to call and make a reservation. I still remember the days you would get a letter from somebody, four months in advance.”

The DisneylandFoward changes figure to come slowly. Attractions linked to such Disney properties as “Coco” and “Avatar” the “Avengers” franchise could entice guests who aren’t even born yet.

That kind of planning, to Patel, is progress.

“Back in the ’70s, the hotels were separate, Disney was separate, the city was separate,” Patel said. “Now, we all work together.”

It’s hard to imagine an Anaheim without its marriage to Disney. Longtime residents suggest the city and the county were going to grow with or without Disneyland. But would Anaheim, sans Disneyland, have pro sports, or a convention center, or dozens of hotel owners like Patel?

Most say no.

“With marriages, there may be tough times. And I think that’s true in Disney’s relationship with Anaheim,” said former city councilmember and Anaheim historian Faessel.

“But the significance of Disney, as (it) grew, was not lost on the city, or businesses, and the residents.”