To understand how longtime frenemies Frank Jao and Tony Lam view Orange County’s Little Saigon, consider this bit of fictional wisdom from another immigrant named Tony, Tony Montana, the guy Al Pacino played in the movie “Scarface:”

“In this country, you gotta make the money first.”

The key word there isn’t money; it’s first.

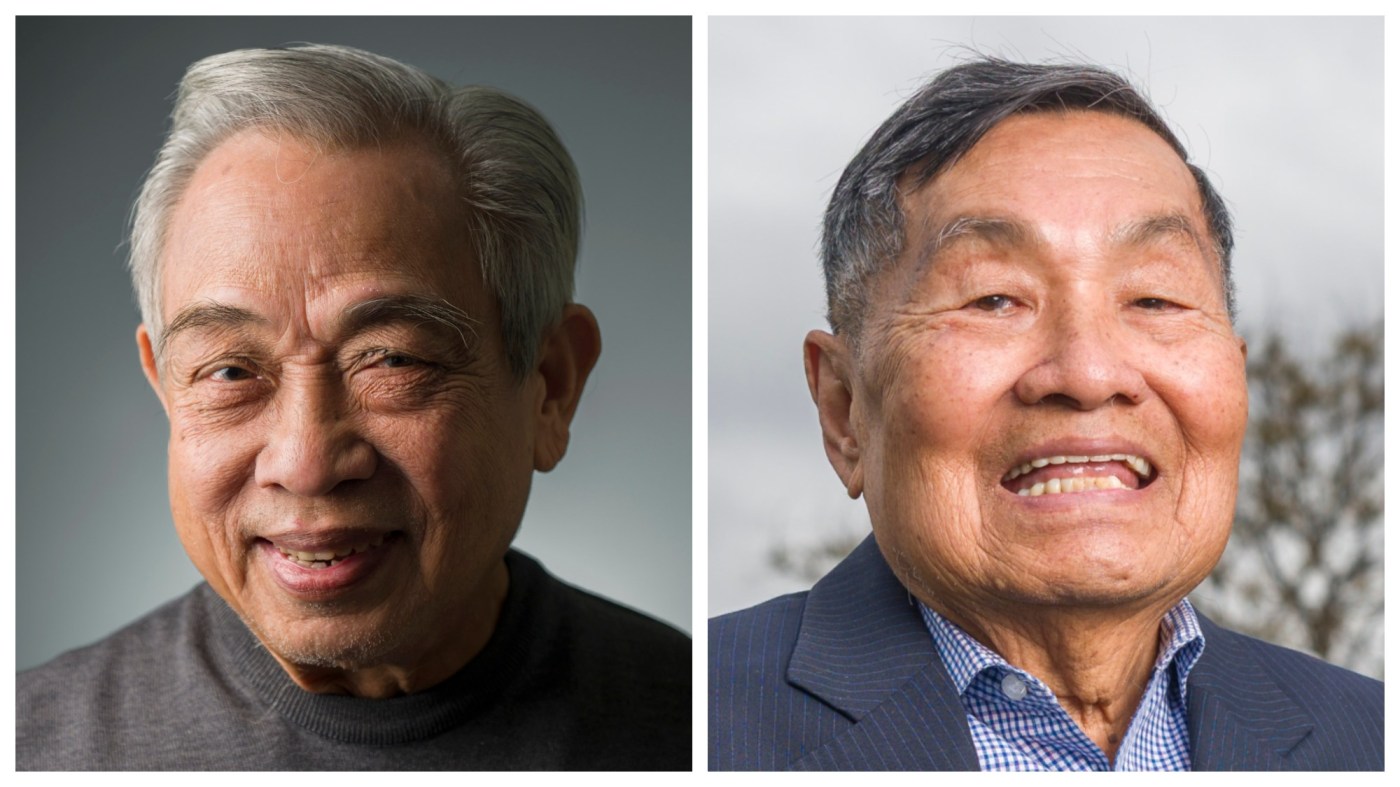

To be sure, Jao, 78, and Lam, 88, both like money. Each has earned enough of it to be considered wealthy (Jao) or solidly comfortable (Lam). It’s meant security and education for their families. It’s meant power and respect within their community. It could even mean – if either man was inclined to enjoy it, which they are not – leisure.

But money has never been the only goal. Instead, to hear both men tell it, money is just part of a bigger and trickier task of building something of real value: a community.

“Vietnamese people came here (and) worked hard. We were smart. We succeeded,” Lam said, loudly, because one ear no longer works so great.

“But we did it together. And because of that, I think, we made something real; a real place, a real home. We didn’t just make the money. We made… “

Then, grinning even wider than usual and spreading his arms to remind you that his tidy Westminster dining nook is part of a much bigger world, Lam added:

“Everything.”

Two paths

If, over the past half-century, Jao and Lam have helped invent Little Saigon – and by all accounts, including their own, they have – they’ve done it in different ways.

Jao has been (and is) the business leader.

In 1987, after nearly a decade spent building strip malls and other commercial developments in Orange County for other (mostly Asian) investors, Jao pooled enough international and domestic funding to build a retail project, the Asian Garden Mall, under the banner of his own company, Bridgecreek Development.

Since then, the indoor-outdoor mall on Bolsa Avenue, currently home to nearly 300 stores and service providers, has become a center for business and culture in Little Saigon. Tết festivals and Tết parades and Tết-themed swap meets start or happen there. Politicians give speeches there. The community’s robust Vietnamese-language media – spanning everything from TV and radio to print news and podcasts – use the place as a backdrop and source generator.

The Asian Garden Mall is even listed as a go-to spot for tourists, and the city of Westminster estimates that more than a half-million shoppers who patronize Asian Garden Mall each year come from outside Orange County.

And though he initially wanted the Asian Garden Mall to be viewed as pan-Asian or even Chinese (he once lobbied for “Asia Town,” not Little Saigon, to be the name for the surrounding community), Jao’s mall has become a very Vietnamese-specific icon.

“Nail salons and the Asian Garden Mall; that’s what I thought about as a kid. A lot,” said Tri Collinson, a 41-year-old Irvine resident and restaurant co-owner who grew up splitting time between a home in the Little Saigon stretch of Orange County and the slightly smaller Little Saigon in San Jose.

“As an adult, I’ve done both,” she added, laughing.

“I’ve been a manicurist. And that was fine. But now I’m also hoping to build something for myself. I want to build a company like Frank Jao built in the Asian Garden Mall. That’s my American Dream.”

Jao has built other properties. Over the decades, he’s been landlord to more than 1,200 local businesses. He’s also worked in other industries and, today, is an investor in everything from manufactured housing to a start-up that links traditional Asian herbal medicines with Western researchers with a goal of developing commercial pharmaceuticals.

A few weeks ago, Jao was in Vietnam, advising a banker friend about the new, less trade-friendly version of the American economy

“We talked about globalization and how you can learn from the old wisdom of the Chinese,” he said. “Time and patience are powerful.”

But building things, he added, remains a passion.

“Real estate is hard work. You have to put your blood into it,” Jao said. “But I always felt it was something I could get my hands on. I still love it.”

As Jao carved out a path for Little Saigon’s business community, Lam did the same in politics.

He seems wired for it.

During their journey out of Vietnam, in 1975, Lam and his family (his wife, Hop, and their six children, then ages 3 to 12) spent time in two refugee camps, one in Guam and the other at Camp Pendleton. At both, Lam wound up organizing the community. In Guam, he launched movie nights and asked radio operators to relay the news they heard on radio, from the BBC and Voice of America, to news-starved refugees.

At one point, the camp leaders asked him to organize a beauty pageant. Lam balked.

“I told them not to do it, that all the women were beauty queens,” Lam said. “My boss said, ‘Tony Lam, you’re a politician.’”

That boss was right.

Even during his first weeks in Orange County, Lam found himself voicing opinions to shape policies. Less than two months after he and Hop and the kids landed, temporarily, at a shared home in Huntington Beach, he and other family leaders gathered in the backyard, talking about how refugees might thrive in their new home.

“I said I thought Vietnamese should make themselves of use,” Lam said. “I thought, in that way, we could become a community.”

Lam eventually started restaurants, including one that specialized in food from northern Vietnam, where he grew up. But he also remained an activist. He helped organize Tết festivals (the first in this country); he lobbied Westminster City Hall on behalf of other Vietnamese residents.

In 1992, he and others hoped to launch a South Vietnamese Armed Forces Day parade, a way to honor the Vietnamese troops who, decades earlier, fought and died with Americans and others in Vietnam. The Westminster council of that era was uninterested, with one member saying, “If you want to be South Vietnamese, go back to South Vietnam.”

Lam was insulted.

“That was racist, I thought,” Lam said, shaking his head.

“So I ran for his seat. And I won.”

Today, a Vietnamese American winning a council seat in Westminster isn’t news. At times, the entire council has been of Vietnamese descent. Last year, Derek Tran became the first Vietnamese American to represent Little Saigon in Congress.

But none of that was true in 1992. When Lam won, he became the first Vietnamese-born politician to hold elected office in the United States.

“I was happy.”

What they share

Their beef, such as it is, dates back 30 years.

In 1995, Jao asked the Westminster city council to float bonds to pay for a bridge that would link his Asian Garden Mall with another of his properties across Bolsa. Lam says the request was denied because the design wasn’t Vietnamese-specific.

“He wanted something to be Chinese or just Asian, and we didn’t. We wanted something Vietnamese. And I said so,” Lam said.

“Frank and I still respect each other, I think,” Lam added. “But that is probably as much as there is.”

If so, it’s odd because the two men share so much.

Both grew up in the northern part of Vietnam and were forced south, early in life, by war. So when they landed in the United States, it was their second stint as refugees.

Both men also spoke English long before coming here, each having worked as translators for the American military and businesses.

Both also had succeeded in Vietnam. Lam owned, among other things, an import company and a shrimp business. The villa he and Hop and the kids lived in in Saigon was later taken over by government officials.

Jao had been supporting himself since he was 14, running a small network of young newspaper delivery workers. By 1975, he was working as a salesman for an American company, the latest in a series of sales jobs.

They both also had, and have, drive.

Jao, in the first months and weeks in this country, worked as a security guard and a vacuum salesman. He also sold condominiums and he studied business at night. Lam, too, held a whirlwind series of jobs, including a brief run as a gas station attendant. When he talks about it, even now, he flexes his right hand as if he’s still working a pump.

Critically, both men were also shaped by a world that no longer exists.

The “Little” in Little Saigon hasn’t been needed for decades. There is no other Saigon. The communists who took the country in 1975 renamed it Ho Chi Minh City. But the pre-communist vision of Vietnam didn’t end, it just relocated to Orange County.

“The Saigon that we knew has been gone since we got on the planes,” Jao said, referring to the military cargo jets that flew him and his wife, Catherine, out of Saigon on April 28, 1975.

Much of what Jao and Lam share is shared by other so-called “first wave” Vietnamese immigrants – who were followed in the 1980s through the early 2000s by people who escaped the country in dire circumstances, often by boat.

That first wave set the tone. Between 1975 and 1980, the Vietnamese population in Orange County grew from something close to zero to 19,333. As of 2023, about 215,000 people of Vietnamese descent – people born there, plus their children and now, their great-grandchildren – lived in Orange County, according to census data.

Both men also share this: They survived, and thrived, for their families.

Jao has two daughters, both born in the United States. He noted, proudly, that both have advanced degrees, in economics and business, one from Stanford and the other from USC. Lam has five surviving children, who grew up mostly in Orange County. The crew includes physicians and business owners and others who have succeeded financially and culturally.

None of those now adult children, both men note, feels anything less than 100% American.

“At one point in time, I served in the Republican Central Committee in Washington, D.C. And I told them that while you are trying very hard to sell to the people that America is anti-discrimination, but you are making a mistake,” Jao said.

“You don’t call people from England the English Americans, or the Germans German Americans,” he said.

“But you pick the Asians and the people from other places, like Mexico, and you say Filipino American and Mexican American and Vietnamese American. That wasn’t just the Republicans, of course, it was everybody,” he said. “And it was discrimination, all by itself.

“We’re all just Americans. All of us,” Jao said. “That’s it.”